Free event with the cost of museum admission....

McHenry County played an important role in fighting another health scourge

Closed in 2011, the 116-acre Camp Algonqin was only one of four camps built in the U.S. during the “Fresh Air in the Country” movement in the late 19th century.

The ongoing war against COVID-19 got me thinking about another battle in the early 1900s.

Known as “consumption,” for how it consumes the body, tuberculosis remains the leading infectious disease killer in the world, claiming 1.5 million lives a year. The McHenry County Department of Health still operates a tuberculosis clinic in Woodstock, which provides chest diagnostic studies, laboratory services, medication and referrals for X-rays.

Similar to COVID-19, tuberculosis typically targets the lungs of victims – who then unwittingly spread the disease in droplets when they cough or sneeze. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1.7 billion people were infected by TB bacteria in 2018 – about 23% of the world’s population.

But as bad as it remains, even after the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s that have largely controlled it in the U.S., at the turn of the century the “Great White Plague” was the leading cause of death here.

Victims often experience weight loss, fever, chills and night sweats, as well as coughing up of blood-tinged sputum, a mixture of saliva and mucus.

Little wonder parents of the inner-city poor were desperate to get their sickly kids out tenement neighborhoods into the fresh air of the country.

In articles for The Atlantic in the 1860s, American doctors promoted the therapeutic benefits from being outside for tuberculosis patients.

H. I. Bowditch argued for the curative powers of “pure air and sunlight,” recounting the story of a 30-year-old woman he had treated for tuberculosis.

“We directed that she should sit out on this piazza every day during the winter, unless it were too stormy,” he wrote. “The balmy influences exerted on her by daily sun and air bath were so grateful her breathing became so much easier after each of them, that, whenever a storm came, and prevented the resort to the piazza, the invalid suffered.”

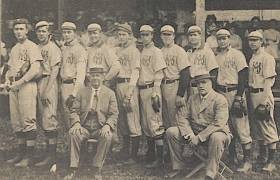

Camp Algonquin in McHenry County was one of just four camps built in the U.S. during the “Fresh Air in the Country” movement. In 1907, the Chicago Tribune donated the riverfront oasis to the Chicago Relief and Aid Society. The camp’s focus was nutrition, exercise and the great outdoors.

Clean air and sunshine were cutting-edge treatments for TB – and evidence exists to suggest both help. Ultraviolet light kills tuberculosis bacteria by damaging its DNA so it cannot infect people and then replicate.

Children too ill to attend Camp Algonquin instead went to a special subset – Camp Harlowarden – to receive proper nutrition and medical treatment. An article in the June 14, 1931, edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that of the 500 children prepared to spend the summer there, some received extra attention.

“The children who were examined yesterday were some of the 76 children from the Stockyards District of the United Charities, whom staff doctors of the Municipal Tuberculosis dispensary and the Elizabeth McCormick Memorial fun have recommended to the camp because of their continued poor physical condition,” the article stated. “They will be housed in the Harlowarden section of the camp and will spend the whole summer under the direction of a physician, nutritionist and the United Charities social workers.”

What began with a collection of tents and the Fox River for washing and bathing, soon evolved into a sophisticated array of cottages and dormitories. A 1929 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map identifies by name and location nearly two dozen buildings within the camp.

The McHenry County Conservation District, which now owns the campground on – reconstituted as the Fox Bluff Conservation Area – worked with the McHenry County Historical Society to save a handful of the 54 buildings. They include the dairy barn, one of three 1909 Tribune dormitories and the recreation building.

•••

If you have been wanting to commit your thoughts to paper about the pandemic but are at a loss on how to get started, the McHenry County Historical Society’s COVID-19 questionnaire provides an easy-to-follow framework for folks to use.

While you may be sick and tired of this virus by now, remember it will be as foreign to future generations as the bubonic plague. We have an obligation to share our thoughts and pictures as part of a permanent historical archive. Only then will MCHS be able to weave these threads into a representative tapestry, conveying the sheer magnitude of this cataclysmic event.

• Kurt Begalka, former administrator of the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum in Union.

Published Dec. 7, 2020 in the Northwest Herald

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.