The Museum will be closed from 4/18 through 4/21. The Library & Office will be closed from 4/18 through 4/20.

- About Us

- Museum

- Preservation

- Research

- Contact Us

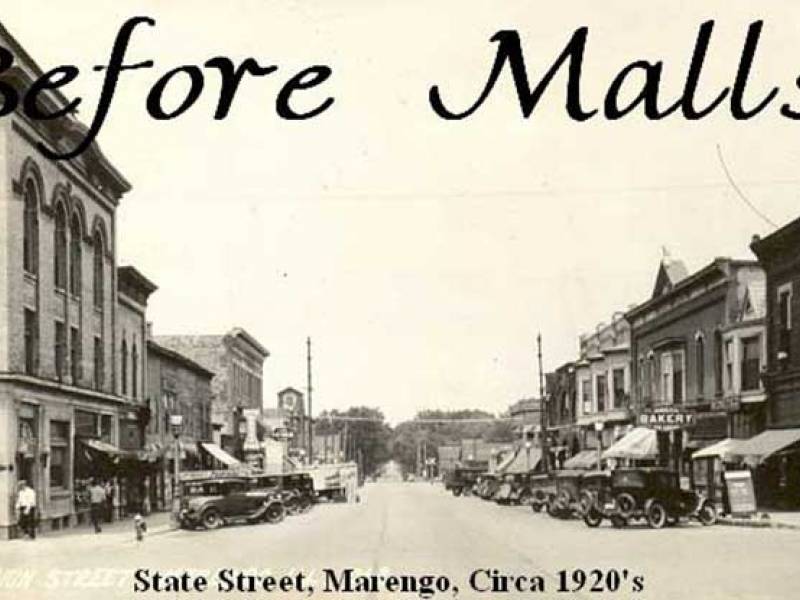

Life Before Malls

You are here

Life Before Series...

For some time now we’ve been contemplating writing a series of focused articles on very specific subjects – the kind of things school children rarely read about in their history text books.

The writings will be made available in paper form as well. Called “The Before… Series.” We are concentrating on the decade of the 1920’s – a time of great change, social upheaval, easy credit, hard roads, electricity, radios, golf.

Yet it was also a time when most McHenry County residents still live on family farms, attended one-room schools and remembered the so-called “Good Old Days.”

The 1920s ushered in the age of American consumerism. With the sacrifices of the Great War behind it, America turned its back on the old and set its face defiantly, if somewhat apprehensively, to the future, to the new and to the modern. McHenry population increased greatly from 1900 to 1929, and businesses grew along with it.

Advertising was revolutionized during the decade. From merely advertising lists of products available, manufacturers saw the possibilities of creating not only new products, but also the need for them. Aggressively pursing this, they defined what it meant to be successful and told the customer what they needed to buy to achieve it. The new was exciting, but there were also underlying uncertainties. Listerine ads ask—Is your breath really fresh—Are you sure about yourself?

People in McHenry County, while embracing the new era, kept much of their day-to-day lives steady and predictable. Farm and town families alike continued to grow many of their vegetables in a back yard garden. Chicken coops were not unusual. Canning fruits and vegetables in season kept many housewives tied to stoves in a hot kitchen in August and September. Rows of beautiful canned peaches, tomatoes, pickles and jams from her labors rewarded the whole family through the winter. Traditional ads showed women demonstrating their love for their families by preparing and serving homemade food. Women were very seldom, however, depicted as indulging themselves by actually eating.

The Campbell Soup Company became a leader in changing this image. They launched a series of ads claiming their soups were more nutritious than the soups made by the housewife. They suggested that furthermore their modern facilities were more sanitary than the dubious cleanliness of the average kitchen. Opening a can of Campbell Soup and enjoying it with your family was more efficient, modern and healthful. The Twenties saw the growth of the brand name product. The Crystal Lake Herald of 1923 ran ads for Armor Star bacon, Maxwell House coffee and Del Monte salmon. The chain store also began its march across the country. F.W. Woolworth, J.C. Penney, Safeway, Kresge and Piggly Wiggly began to exert pressure on the “Ma and Pa” stores. Schueneman Bros. urged customers to “buy at home—your dollar buys more value here than anywhere else.”

McHenry County in the Twenties was still dominated by the specialty store. Most any item that a family needed could be had by going downtown. Most downtown areas included a department store, hardware, pharmacy, bakery, meat market, grocery store, ladies’ dress shop, millinery , and five-and-dime. For example, in 1920 Woodstock had two bakeries, four stores offering meat markets, four clothing stores, two retail dry goods, two furniture, three hardwares and many more shops. Smaller Harvard had two clothing stores, one retail dry goods, one furniture, two hardwares, two meat markets, and two bakeries plus other goods and services. Most every town had a dressmaker, a tailor and a shoe repairman who also sold and mended harness “in time for your spring plowing needs.” Proprietors often were very knowledgeable in the products they offered, having been in that line of business for generations. An example of this was Samter’s Store for men in Marengo. The store was founded by G.A. Samter in 1853 after arriving from Germany. When he retired in 1897 the store was managed by his son until 1917. Then a grandson, Harry Buell took over and ran the family business for 54 years until it was sold in 1972. The “Reliable Clothier” was a Marengo mainstay for 119 years.

Elite Shop of Marengo in 1927 proudly announced that their new owners “with their pleasing personalities and friendly manners…are operating…with the welfare of their customers first at heart…” When, in 1921, the Piggly Wiggly chain introduced a new way of shopping with self-service lanes scientifically laid out, customers felt somehow subtly diminished in importance. Service was the order of the day. Not only Marshall Field sought to “give the lady what she wants.”

Before electric refrigeration, ice boxes in the home kept food fresh but necessitated more frequent shopping. Grocery stores accepted orders by phone and delivered to the home that same day. Crystal Lake Grocery store sold Marshalls best flour for $1.85 in the store or $1.09 delivered. Most stores delivered for free. When refrigeration became common, grocery shopping could be done once a week. A shopping trip required the lady to be dressed properly. No one wanted to be seen in public in less than their best. At the store, the customer presented the clerk with a list of items desired, or told them what was needed. The clerk then fetched the items for the customer and bagged them. Bagging was carefully done. In grocery stores, especially, heavier items were placed in the bottom of the bag and braced against each other so they would not shift when the bag was lifted. Purchases were carried to the customers’ car or carriage.

Stores were closed Wednesday afternoons, open until nine on Saturdays. Everyone was closed Sundays, of course. Downtown Saturday night was a big event in McHenry County towns. Parking spaces were at a premium. The noise level coming from downtown rose steadily through the evening as cars arrived, people went from store to store, stopped to chat and catch up on the latest news. Stores, ice cream parlors and movies theatres all did a brisk business. One Saturday night in Harvard in 1922 had 620 autos and 22 horse drawn carriages clogging the streets and maneuvering for parking space.

Women continued to make many items of their own and their families’ clothing by hand. Patterns and material were readily available at the local five and dime. For social occasions, however, a purchased dress in the latest style was required. Mail order dresses were available by catalog. The Chicago Mail Order co. offered in 1921 a beaded silk crepe dress for $6.98. The local ladies’ dress shop was the mainstay for dress shopping for most people. The owner of such a shop took pride in having on hand just what was wanted by a long-term customer. Fitting was free. The Corner Shop of Crystal Lake, catering to the conservative tastes of McHenry County ladies (or perhaps just in possession of an overstock) announced in a 1923 ad “what every woman knows---that corsets are going to be worn just as much as ever.” The corset, however, was on the way to extinction. The boyish figure, slim and flat-chested, was the new fashion. Flapper looks were viewed initially with some suspicion. It was said that girls were becoming too thin, wearing themselves out doing the Charleston.

Roads, some newly paved, railroads and electric lines crisscrossed the county, making the excitement of out-of-town shopping within reach of more people, but still sufficiently noteworthy to merit an item in next week’s newspaper. “Mrs. Henry Jones spent Thursday shopping in Woodstock.” Better yet was a train ride to Chicago for a day spent at Marshall Field’s.

The shopping and buying of the Twenties was financed increasingly by the use of credit. The age of the easy monthly payment was born. Public Service Co. would deliver a Federal electric washing machine to county residents for $5 down and monthly payments of $7.50. A Federal electric vacuum cleaner could be had for $1.40 down. J.P. Kroger of Crystal Lake offered a Ford Touring car (total price $298 f.o.b. Detroit) for “a small down payment and the balance on easy terms.”

The rising amount of debt did not concern most people. A player piano was $12 a month, and a refrigerator was $10 a month. The Music Company would gladly arrange payments on a modern, new Victrola music machine. The Corner Shop had a special showing of hats of “original and Parisian cleverness.” Excitement was in the air. An easier life could be paid for as we go. In the mid-1920s, the hard times seemed all behind them. And they were---for a while.

by--Jean Nigbor

- Research Library

- • Reference & Archival Materials >

- Sears Home Map of Crystal Lake

- Heritage farms

- Historic Links

- How to Research Your Property

- • Forgotten McHenry County >

- • Life Before Series >

- • Statistics >

We Want You!

Volunteers are needed for various other projects! If you are interested in local history or have other skills you can contribute, please complete our Fillable Volunteer Form. If you have any questions, please phone our office at 815-923-2267.

Sign up for the free MCHS Monthly Newsletter.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.